Bopyrid Isopod Parasites of Shrimps

Shrimps, like all animals, suffer from a variety of parasites (e.g., Overstreet, R.M. 1978. Marine Maladies? Worms, germs, and other symbionts from the northern Gulf of Mexico. Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium 78-021, 140 pp.) One of the most noticeable shrimp pests is another crustacean group, the bopyrid isopods. The most important effect of these parasites is the castration of their hosts. Female shrimps infected with a bopyrid usually have complete reproductive failure; such females do not produce or spawn eggs (e.g., O'Brien J and P.M.Van Wyk. 1985. Effects of crustacean parasitic castrators (epicaridean isopods and rhizocephalan barnacles) on growth of crustacean hosts. Pp.191–218 in: A.M. Wenner (ed) Crustacean issues 3: Factors in adult growth. A.A. Balkema, Rotterdam,).

I have been fascinated by bopyrids since graduate school. For a project in Dr. Dixie Lee Ray's summer marine ecology course at the Friday Harbor Marine Laboratories in 1970, I sampled populations of the thorid shrimp Heptacarpus paludicola from Zostera seagrass beds in the Argyle Lagoon on San Juan Island (Washington). Nearly 50% of the female population was parasitized by the abdominal bopyrid Hemiarthrus abdominalis. That is a 50% reproductive loss for that population! It can be even higher: J.T. Beck reported up to 100% reproductive failure in some populations of Palaemonetes paludosus!! ( Beck, J. 1979. Population interactions between a parasitic castrator, Probopyrus pandalicola (Isopoda: Bopyridae), and one of its freshwater shrimp hosts, Palaemonetes paludosus (Decapoda: Caridea). Parasitology 79: 431-449)

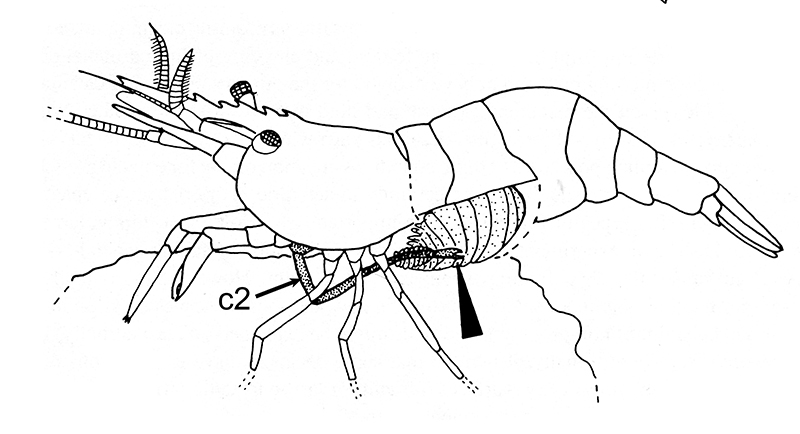

Most bopyrid species occupy the gill chamber of the host, deforming its gill cover into a noticeable bulge, although some othe bopyrid species cling to the underside of the shrimp's abdomen. The parasite occurs as a male-female pair: a large bulky female with a tiny dwarf male attached to the females's posterior end. The female's mouthparts face outwards, against the inner wall of the shrimp's gill cover. It sucks and feeds on the body fluids of the female; it is little wonder that a parasitized female shrimp has little or no energy to produce eggs. It is not known if and how the dwarf male parasite feeds (perhaps a hyperparasite of its female partner?). Although the parasite pair is surrounded by host cuticle, which is shed during molting of the shrimps, Cora Cash and I (1993) showed how the parasite pair maintain themselves inside the newly molted gill chamber in spite of molting by the host, and how the parasite reproductive cycle is linked to the molting cycle of the shrimp (see Bauer publications).

|

|

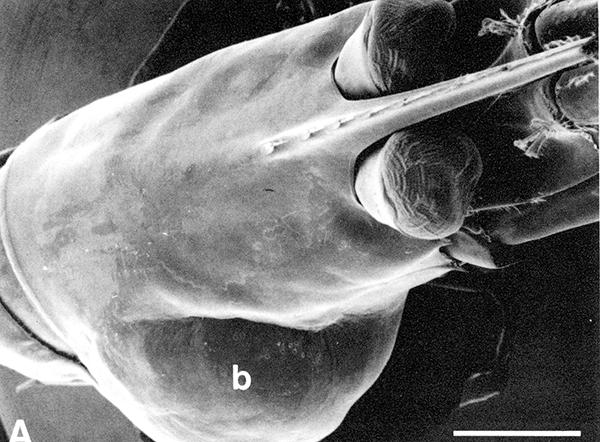

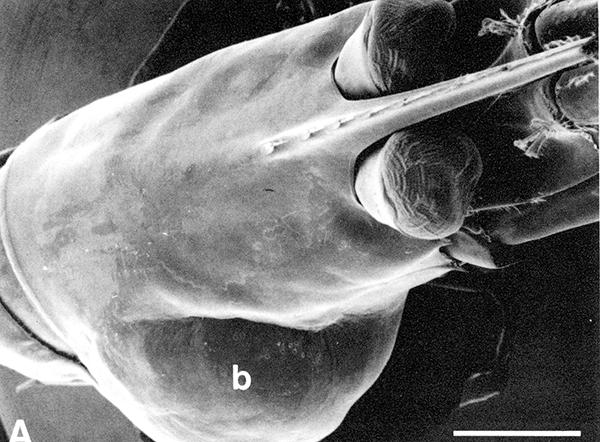

| Palaemon (Palaemonetes) pugio with a Proboyrus pandalicola bopyrid female (p, large visible object whose embryo incubation chamber is surrounded by dark marsupial plates.) The dwarf male is the dark cylindrical object just anterior to the parasite female brood chamber). | Bulge (b) of shrimp carapace caused by the parasite Probobyrus pandicola (from Cash and Bauer, 1993). |

|

|

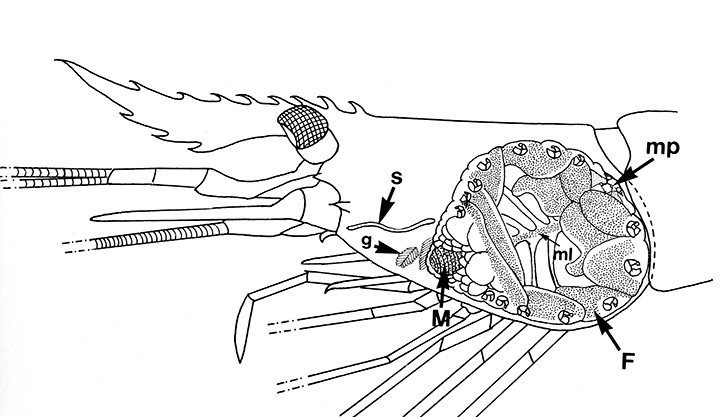

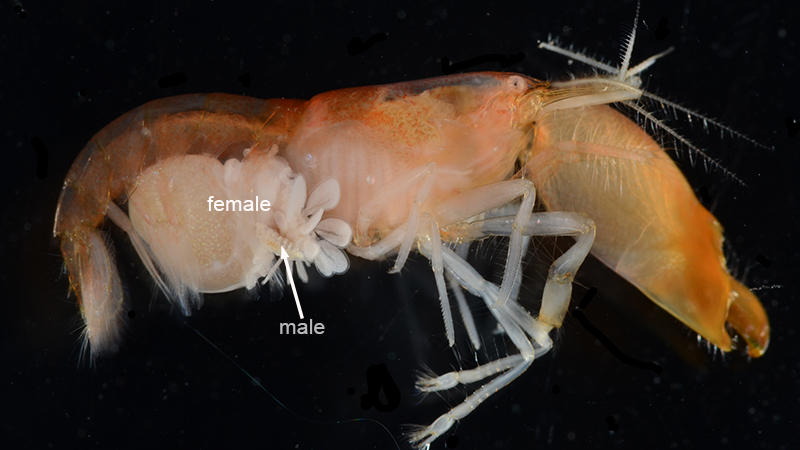

| Diagram of Probopyrus female (F) and dwarf male (M) inside gill chamber of P. pugio (mp, female mouthparts; g, a gill; from Cash and Bauer (1993). | Abdominal bopyrid female and male pair attached to underside of a Synalpheus sp., occupying space where the female shrimp would incubate its embryos (photo courtesy of Arthur Anker) |

|

|

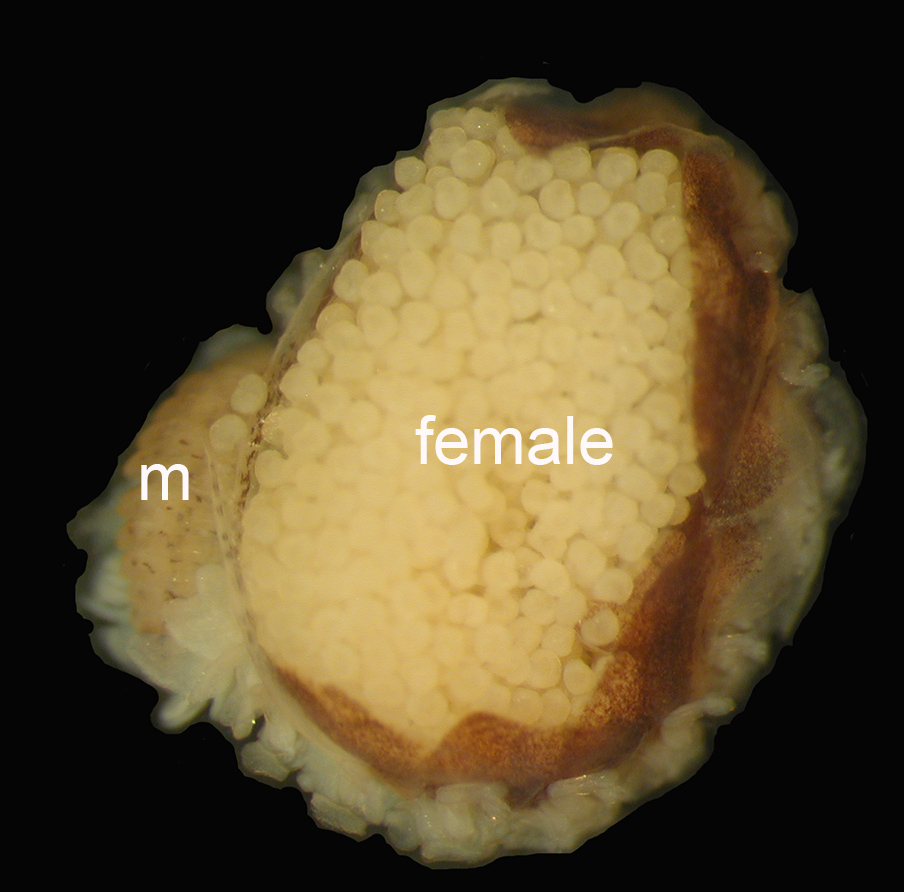

Ambidexter symmetricus female with branchial bopyrid Urobopyrus processae inside the gill chamber; the female's incubation chamber is full of developing embryos. (from Rasch and Bauer (2015); photo by Jennifer Rasch) |

Male (m) and female U. processae. The bopyrid male is attached to the bopyrid female's abdomen; the female's maruspium is full of developing (early stage) embryos. On the shrimp, the posterior end of the female (with male) is situated anteriorly in the shrimp's gill chamber; the female's anterior end with mouthparts are pointed posteriorly in the shrimp's gill chamber (from Rasch and Bauer, 2015) |

One might ask how the shrimp, which is so efficient at cleaning itself, allows the bopyrid to attach and grow on it. The shrimp apparently accepts the parasite as a part of its body, as it grooms and cleans the parasite body as it does its own. How the parasite accomplishes this is unknown (hormonal?).

Although in most cases parasitized shrimp females produce no eggs, occasionally a small number of fertilized embryos share the female's incubation chamber with the parasite pair under her abdomen (see photo below by Eva Toth; a good reference for this is: Hernáez et al., 2010. Fecundity and effects of bopyrid infestation on egg production in the Caribbean sponge-dwelling snapping shrimp Synalpheus yano (Decapoda: Alpheidae). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 90: 691–698).

|

|

| Synalpheus female with abdominal bopyrid parasite but also with a few remaining embryos of its own under the abdomen. The femal bopyrid is the large pale pink mass below the shrimp abdomen (the parasite brood chamber filled with its embryos); the vertical cylindrical object just anterior to the female parasite is its male partner. Although most bopyridized shrimps do not produce embryos, this female does have some (the large dark oblongl structures posterior to the parasite; photo courtesy of Eva Toth) | A female Heptacarpus paludicola grooming an abdominal bopyrid growing beneath the abdomen. Like gill-chamber bopyrids, this abdominal species, Hemiarthrus abdominalis, is apparently accepted as a part of the shrimp's body, or it perhaps it mimics a mass (brood) of shrimp embryos which female shrimps groom during embryo incubation. (from Bauer, 1989 review of grooming in decapods) |

There are many unanswered questions about bopyrids (good research projects!): feeding and nutrition by both male of female, control of the host, insemination of the female parasite by the dwarf male among other topics.