Where Your

Philosophy

Professor

Is Coming From

The following points should help you understand where your

philosophy

professor

is coming from:

Philosophers

care

more

about your reasons than about whether you "get the right

answer."

Philosophers

care

more

about your reasons than about whether you "get the right

answer."

You're not

expected to solve all the difficult

questions in

philosophy in your first philosophy course, any more than a

physics

professor

would expect you to be able to solve all the perplexing

problems of

contemporary

physics during your first physics class. One thing which

makes

philosophy

seem so strange at first is that most people believe they

have already

solved the perplexing problems of philosophy before they've

ever taken

the course. For example, most people have an opinion about

an issue

like

abortion or the existence of God, and they believe they are

right. By

contrast,

few people believe they have already discovered the correct

answer to

the

most perplexing problems of physics. However, many

philosophical issues

are really no easier or less complex than the most difficult

problems

in

physics. Knowing this, philosophy professors tend to begin

with the

assumption

that the answers to philosophical questions such as the

existence of

God

or the morality of abortion are as yet unknown. Moreover,

they do not

expect

you to be able to solve them while taking your first

philosophy course.

As a result,

philosophy professors tend to be more concerned

about teaching

you how to philosophize, that is, how to reason well about

philosophical

issues, than they are about what answer you arrive at.

This is not to say

that which answer you arrive at is

unimportant. After

all, the whole point of doing philosophy is to discover

interesting and

useful truths. But we do not expect you to be able to defend

your

answers

to philosophical questions the way someone who has thought

hard about

them

for 20 years can.

Nothing

is sacred.

Nothing

is sacred.

A good

philosopher is willing to question anything

and everything,

even the methods of philosophy itself.

There

often seem

to be persuasive reasons which support both sides of an issue.

There

often seem

to be persuasive reasons which support both sides of an issue.

If you

approach philosophical arguments with an open

mind,

you'll quickly come to see this. If you've discussed several

controversial

philosophical issues in class and you don't see this, odds

are that

you're

not giving the opposing side the credit its due. As a

result, you may

not

see the point of discussing the views of the opposing side.

If this is

the case, try being more open to opposing views. One way to

do this is

to imagine that something important to you, such as winning

a court case or

getting

a great job, depends on your convincing someone of the

opposing point

of

view. What would you say to prove to them that the view you

personally

disagree with is actually true? How effective could you make

your

arguments

for your view?

That there seem to

be persuasive arguments for opposing

sides of a view

does not prove that there is no correct view. After all, if

nothing

plausible

could be said for the opposing side of an issue, it wouldn't

be an

issue

to begin with! What makes an issue an issue is that there is

something

to be said for both sides.

Where it seems

that equally plausible reasons conflict, we

have an indication

that someone's reasoning has gone astray in some subtle way.

The goal

will

be to figure out where the mistake is.

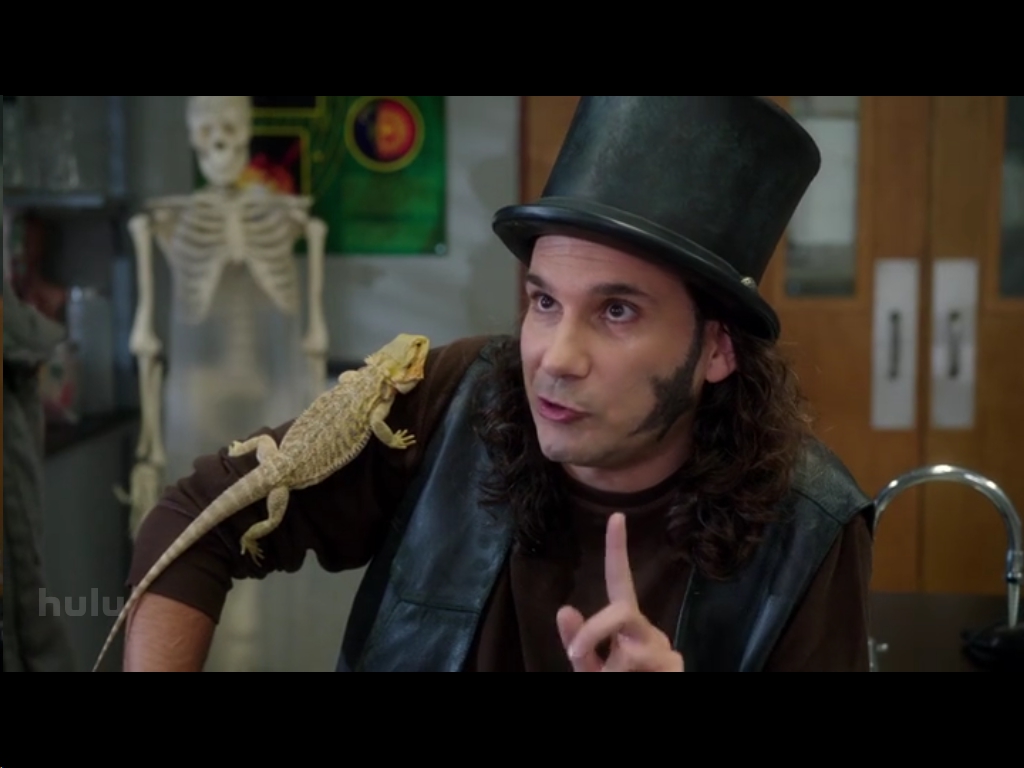

Proper Classroom Deportment Never

Hurts

Proper Classroom Deportment Never

Hurts

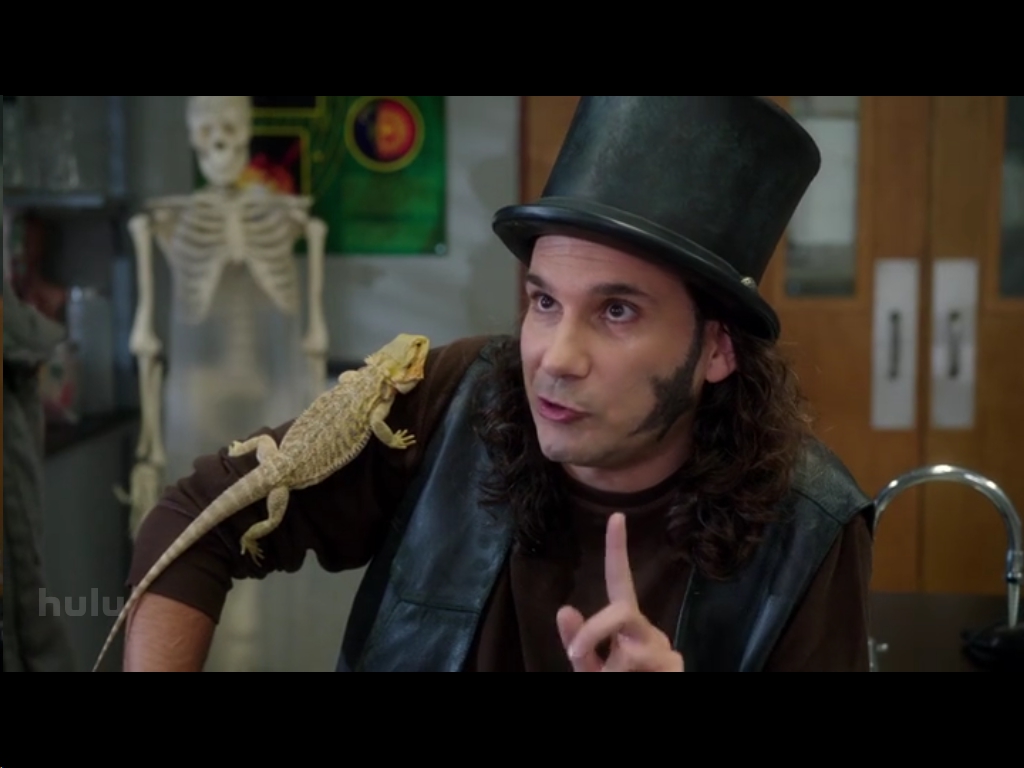

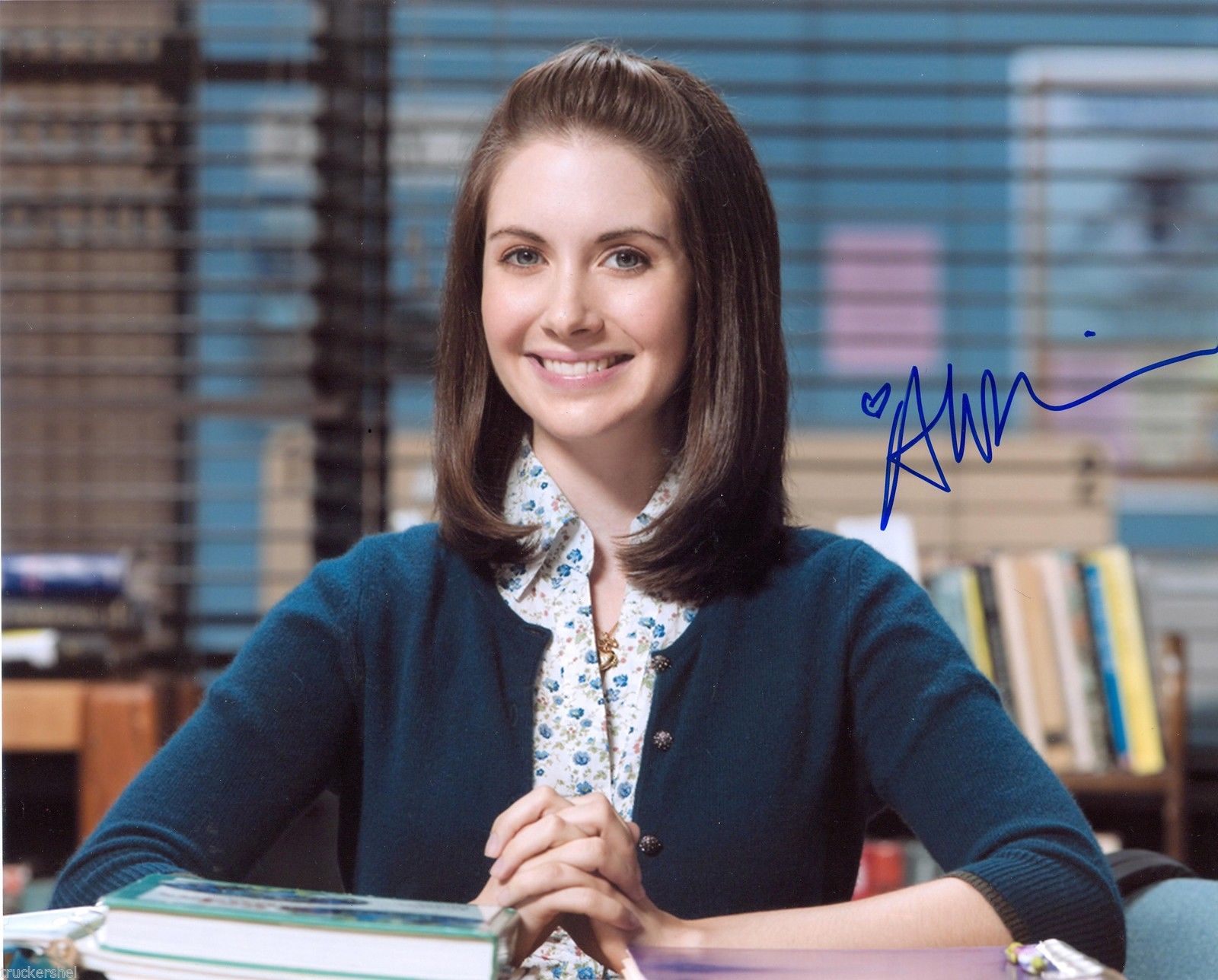

Good:

Not So Good:

Additional

Resources

Additional

Resources

Douglas J.

Soccio, How To Get The Most Out Of

Philosophy,

(Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing, 2006).

"What

Is

Philosophy?" by Keith Korcz.

Philosophers care more about your reasons than about whether you "get the right answer."

You're not expected to solve all the difficult questions in philosophy in your first philosophy course, any more than a physics professor would expect you to be able to solve all the perplexing problems of contemporary physics during your first physics class. One thing which makes philosophy seem so strange at first is that most people believe they have already solved the perplexing problems of philosophy before they've ever taken the course. For example, most people have an opinion about an issue like abortion or the existence of God, and they believe they are right. By contrast, few people believe they have already discovered the correct answer to the most perplexing problems of physics. However, many philosophical issues are really no easier or less complex than the most difficult problems in physics. Knowing this, philosophy professors tend to begin with the assumption that the answers to philosophical questions such as the existence of God or the morality of abortion are as yet unknown. Moreover, they do not expect you to be able to solve them while taking your first philosophy course.Nothing is sacred.

A good philosopher is willing to question anything and everything, even the methods of philosophy itself.There often seem to be persuasive reasons which support both sides of an issue.

If you approach philosophical arguments with an open mind, you'll quickly come to see this. If you've discussed several controversial philosophical issues in class and you don't see this, odds are that you're not giving the opposing side the credit its due. As a result, you may not see the point of discussing the views of the opposing side. If this is the case, try being more open to opposing views. One way to do this is to imagine that something important to you, such as winning a court case or getting a great job, depends on your convincing someone of the opposing point of view. What would you say to prove to them that the view you personally disagree with is actually true? How effective could you make your arguments for your view?Proper Classroom Deportment Never Hurts

Additional Resources

Douglas J. Soccio, How To Get The Most Out Of Philosophy, (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing, 2006).